25.04.2020

Old And New Media: Disinformation in Times of the Corona Crisis

- We asked our respondents to evaluate five statements in terms of their truthfulness: less than half of the respondents identified all disinformation statements correctly.

- Almost one in eight respondents were unable to identify any of the statements as disinformation.

- Even though uncertainty about the truthfulness of a statement plays a more crucial role than the convinced belief in disinformation, this still reveals a worrying picture.

- People who use the public broadcaster (ORF) or the quality newspaper, Der Standard, as a source of information in the corona crisis, are more capable of identifying disinformation.

- People who use commercial television, the tabloids Österreich or Kronen Zeitung, WhatsApp, Instagram, or YouTube as a source of information are less capable of identifying disinformation.

By Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Noelle S. Lebernegg und Hajo G. Boomgaarden

The current situation not only leads to uncertainty among the population, but also to an increased search for information. However, this combination is a potential breeding ground for the spread of disinformation. As a consequence, the WHO laments an “infodemic” associated with the current pandemic, i.e., the uncontrolled spread of false information and conspiracy theories about the virus, protection against it, or even its origin. Respectively, the Austrian Federal Ministry of the Interior warns explicitly against such misinformation about the coronavirus while particularly referring to its spread via new media (especially social media). In this regard, it was shown that instant messaging services such as WhatsApp are a popular platform for the dissemination of such messages. According to some experts, professional journalism, especially a strong public broadcasting service, can represent an essential corrective.

In a previous blog on media use during the crisis, it was shown that media usage is, in general, extraordinarily high. More specifically, it was found that public broadcasting is used particularly often. However, Austrians also use social media platforms such as WhatsApp or Facebook as a source of information. The present article focuses on two questions: First, do citizens identify disinformation about the coronavirus? Secondly, in how far is this capability related to their media use, i.e., the media used as a source of information about the corona crisis? For this purpose, we primarily use data from the second wave of our panel survey.

When One Begins To Doubt, Disinformation Has Already Triumphed

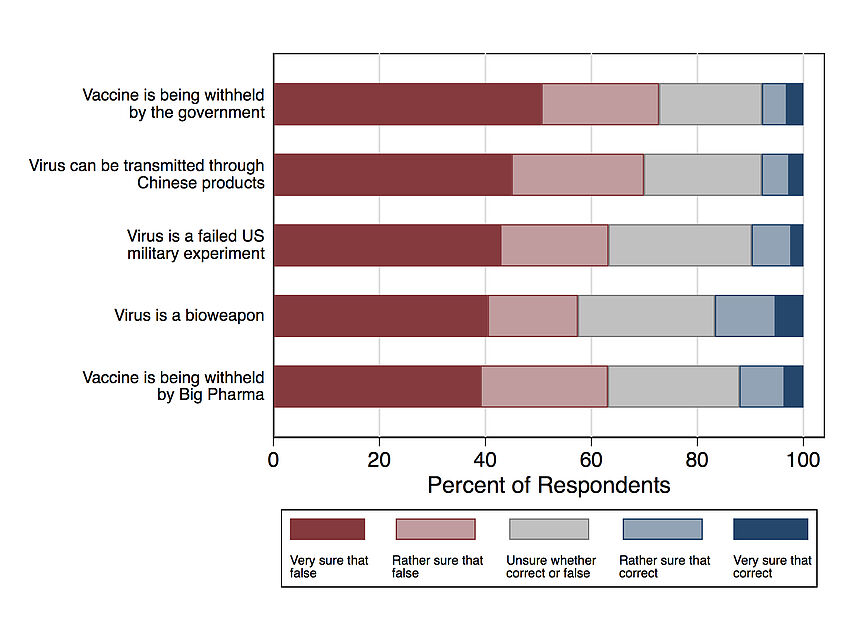

To get to the bottom of the spread of false information among Austrians, we asked our respondents to assess several statements in terms of their accuracy. Five of these statements are typical examples of disinformation in times of the corona crisis. They form the basis for our further analyses (Figure 1).

First, some good news: an average of about 65.3% of our respondents correctly identified the statements as disinformation, i.e., they are "very sure" or "rather sure" that they are false. The respondents are most certain about whether a vaccine is being deliberately withheld by the government (72.8%). In comparison, they had the most difficulties with the claim that the coronavirus is a biological weapon. Only 57.5% of the respondents correctly identified this statement as disinformation. However, a closer inspection of the data also shows that only 40.7% of the respondents were able to identify all statements correctly as disinformation. This also means that 59.3% of the respondents were "unsure" about at least one disinformation, or even were "rather sure" or "very sure" that it was actually true. Hence, the majority of the respondents had difficulties with at least one statement, and almost one in eight respondents (12%) could not even identify any of the five items as disinformation.

Although among those who could not unmask our false statements, the number of uncertain respondents (i.e., people answering "unsure whether correct or false") was generally much higher than the number of people actually being convinced of the disinformation’s truthfulness, these figures are still worrying. If one begins to doubt, disinformation has already reached its goal.

ORF-Refusers And YouTube-Users Are Most Disinformed

To investigate a potential connection between the inability to identify false information and the use of specific media, we asked respondents to what extent they used a variety of different media as a source of information about the corona crisis.

Since media use during a crisis is extremely complex and can be linked to numerous additional factors, we conducted a so-called multivariate regression model (see methodological notes at the end of the paper). In this model, we examined the relationship between media use and the degree of disinformation of the respondents (i.e., their inability to identify disinformation as such).

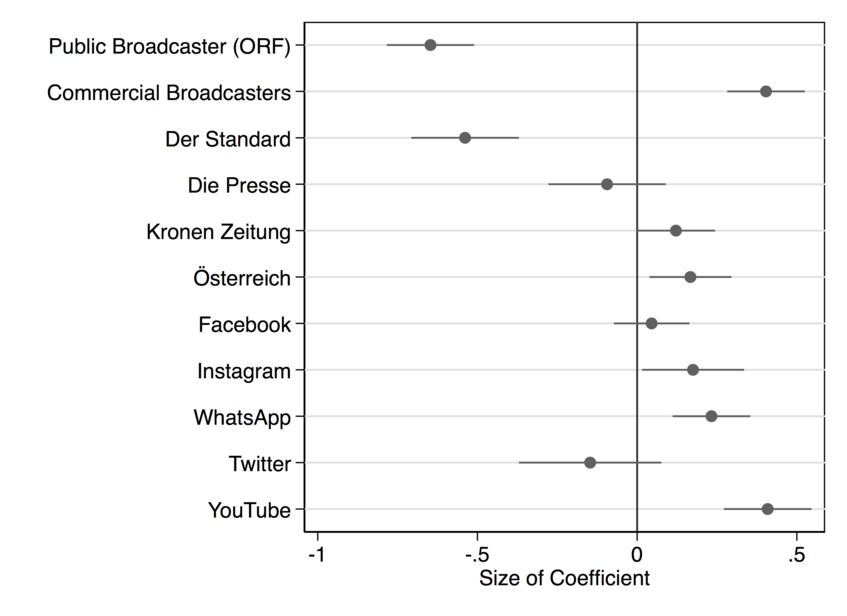

Our analyses show that those who obtain information more than once a week via the public broadcaster ORF or the quality newspaper Der Standard are less susceptible to disinformation. At the same time, it also shows that respondents who keep themselves informed via commercial television news, the tabloids Österreich or Kronen Zeitung, the instant messaging service WhatsApp, the platform Instagram or the video portal YouTube are significantly more disinformed.

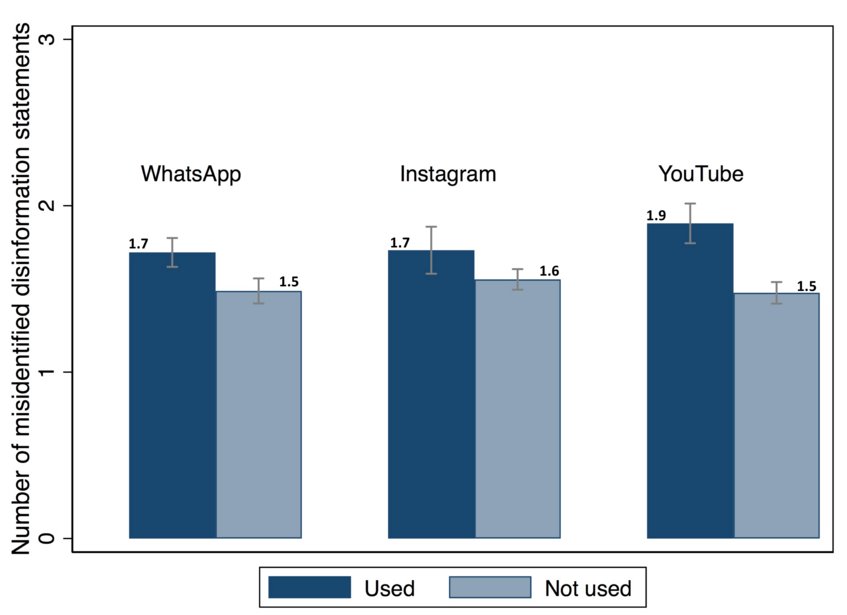

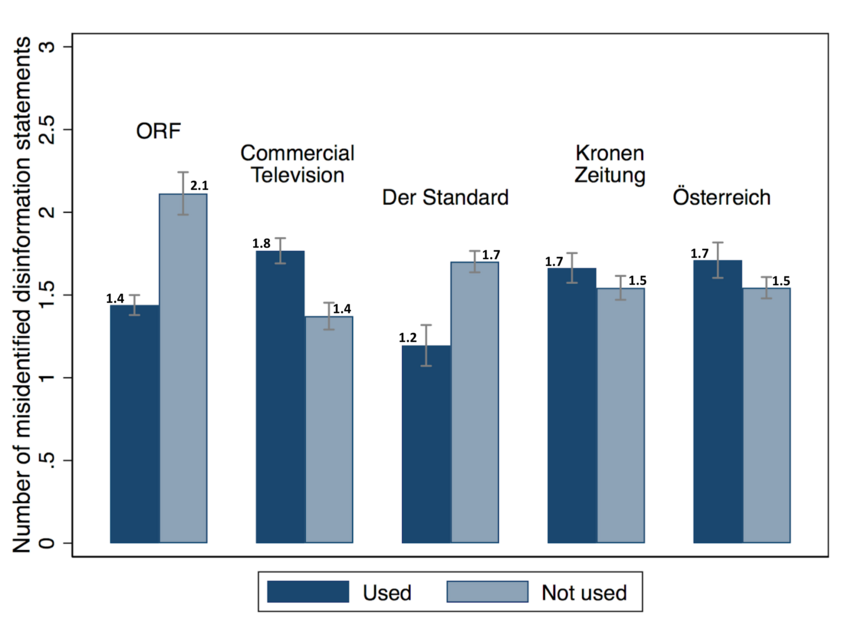

In Figures 2a and 2b, we compared the degree of disinformation of participants who use specific media as a source of information with that of those who do not. Indeed, people who keep themselves informed via ORF, for instance, identify an average of 1.4 statements as false. Those who do not use ORF as a news source are either unsure about an average of 2.1 disinformation statements or consider them to be correct. YouTube users show the reverse pattern. Those using YouTube as a source of information on the coronavirus are either unsure about 1.9 statements or think that the disinformation could be correct. In comparison, those who do not use YouTube as a source of information only misidentify an average of 1.5 of the five disinformation statements.

Figure 2a: Number of unrecognized disinformation statements by information source - Old media (Notes: Field time: 03-08 April 2020, N=1,559 respondents (14 years and older), 1,351 valid values, data weighted, representative for the Austrian population. Mean values predicted on the basis of the regression model; see methodological notes).

Figure 2b: Number of unrecognized disinformation statements by information source - New Media (Notes: Field time: 03-08 April 2020, N=1,559 respondents (14 years and older), 1,351 valid values, data weighted, representative for the Austrian population. Mean values predicted on the basis of the regression model; see methodological notes).

A Call to Old And New Media

In sum, it can be said that although the proportion of convinced disinformed people is rather low, this is not yet a reason for relief as the degree of uncertainty about the facts is nevertheless relatively high within the population. If disinformation sparks doubt amongst fellow citizens about whether the government holds back a vaccine, the disinformation has already achieved its goal.

Hence, there is still quite some need for information within the population. However, where can we, or must we start tackling this problem? Taking a look at the degree of disinformation among users of different sources of information shows that regular users of the ORF or the daily newspaper Der Standard are less prone to disinformation. In contrast, those using commercial television, the tabloids Kronen Zeitung, or Österreich or social media such as WhatsApp, Instagram, or YouTube to obtain information about the coronavirus seem to be more susceptible to disinformation. Similar results were reported by a study of the Management Center Innsbruck, which did not deal with corona disinformation, but with corona knowledge. They showed that the increased use of social media, as well as private television, is associated with lower corona knowledge. In comparison, the use of ORF is associated with higher knowledge.

What next? Although we cannot draw any conclusions about the extent to which the single information sources actively disseminate or fight disinformation, private television, as well as the daily newspapers Österreich und Kronen Zeitung, are well-advised to invest in the clarification of disinformation as they are those who reach the disinformed most likely.

Where platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have reacted quickly and rigorously to the dissemination of corona disinformation, their siblings WhatsApp, Instagram, and YouTube still have some potential for development. In any case, there is one thing we can be sure about: As long as the corona crisis is not over, the "infodemic" will not be entirely over either. To overcome both, old as well as new media will have to do their part.

Jakob-Moritz Eberl has been a post-doc at the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna since April 2017 and a member of the Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES, Media Side) since 2013. He is also an associate researcher at the Vienna Center for Electoral Research (VieCER) and deals with questions on media effects, media trust and voting behaviour.

Noelle Lebernegg is a University Assistant (Prae-Doc) at the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna and an associate researcher at the Vienna Center For Electoral Research (VieCER). She focuses on the impact of political communication and media on public opinion and voting behaviour.

Hajo Boomgaarden is Professor of Methods in the Social Sciences at the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna and currently Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences. His research focuses on the presentation and impact of politics in the media.

Methodological Note

To identify various possible factors influencing the respondents' degree of disinformation, we calculated a so-called multivariate regression model, taking into account not only media use but also other individual-level factors such as age, gender, education, and ideology. This is important in order to examine differences resulting from the differing social composition of different media audiences. The coefficients of a binomial regression model are presented in Figure A1. Media use is coded as a dichotomous variable, i.e., the value 1 was entered if the information source was used more than once a week; otherwise, the value 0 was entered. The dependent variable is the degree of disinformation. This is the sum of all incorrectly identified statements, i.e., the degree of disinformation is 0 if all five statements were identified as "rather false" or "definitely false"; the degree of disinformation is 5 if all five statements were answered with "unsure whether correct or false," "rather correct" or "very sure that correct." If the 95% confidence interval (i.e., the antennas on the circle symbol) exceeds the 0 line, there is no statistically significant correlation between the use of the respective information source and the degree of disinformation. The more positive the coefficient, the more disinformed are the users of this information source. The more negative the coefficient, the less disinformed are the users of this information source.

Figure A1: Relationship between information behavior and degree of disinformation (Remarks: Field time: 03-08 April 2020, N=1,559 respondents (14 years and older), 1,351 valid values, data weighted, representative for the Austrian population).

Related Blog Posts

- Blog 4 (EN) - Old and New Media: Media Use in Times of the Corona Crisis

- Blog 12 (EN) - Most people take the situation seriously. But who are the Coronavirus skeptics?

- Blog 15 (EN) - Of Misunderstood Snoopers and Other Anti-Coronavirus-Activists

- Blog 40 (EN) - Audience Expectations of Coronavirus Reporting: From Watchdog to Lapdog?