18.04.2020

Of Misunderstood Snoopers and Other Anti-Coronavirus-Activists

- There are different interpersonal situations in which one may take (communicative) action and demand responsible behavior from their fellow citizens during the Corona crisis. We call this Anti-Coronavirus-Activism.

- The extent of Anti-Coronavirus-Activism in Austria is rather modest.

- However, 18% sometimes consider reporting people to the authorities if they do not comply with lockdown measures.

- These people have a very high perception of danger and a strong sense of community.

- The blanket attribution of a "snooper" mentality (Blockwart-Mentalität) does injustice to this group.

By Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Julia Partheymüller, Noelle S. Lebernegg und David W. Schiestl

These last few weeks have probably been the most unusual of our lives so far. The pandemic has not only had an immense impact on all our everyday lives, but also on the way we interact with each other. Everyday things, such as going to the supermarket, may pose a considerable health risk, while other habits, such as meeting friends or family, are even prohibited.

This time brings out the best in many fellow citizens. They care for each other and do not want to let anyone down; a new feeling of solidarity seems to arise. With all the new found selflessness and social cohesion, however, a different picture emerges as well. While it began with shaming people on social media who do not adhere to the lockdown measures (e.g. keeping distance in parks), people have started filing an increasing number complaints with the local police.

First concerns arise as to whether we are at the beginning of a new police state. What motivates these supposed snoopers (Blockwart)? Do they enjoy punishing, spying and denouncing others? Or are they driven by other motives? These are precisely the questions we are trying to answer with the data from the third survey wave of the Austrian Corona Panel Project.

Few and misunderstood snoopers?

In everyday life there are different interpersonal situations in which one may take (communicative) action and demand responsible behavior from their fellow citizens during the Corona crisis. In order to compare these different types of Anti-Coronavirus-Activism, we asked respondents whether how much they agreed to four specific statements; please note that we borrowed the first three from a study by the Johannes-Gutenberg-University Mainz.

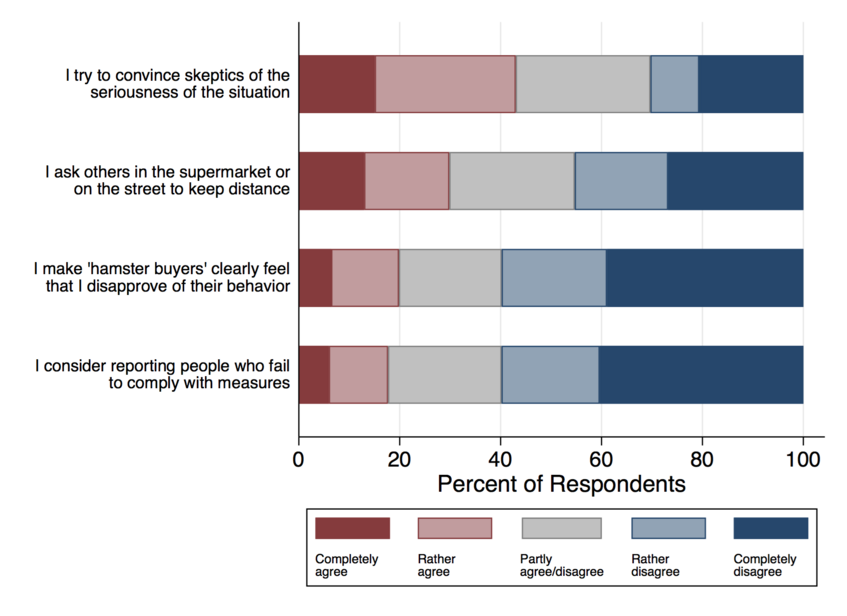

Our data shows that Austrians do not appear to be exuberant Anti-Coronavirus-Activists (Figure 1). They are most willing is to engage in discussions to convince skeptics of the seriousness of the crisis (43% answered "fully agree" or "rather agree"). Another 29.8% are willing to ask other people to ask people to keep distance when shopping or on the street. The percentage of respondents who let “hamster buyers” in the supermarket feel that they disapprove of their behavior is significantly lower (19.8% answered "fully agree" or "rather agree"). Only a minority consider reporting other people to the authorities if they do not comply with the lockdown measures (17.7%).

Figure 1: Willingness to engage in Anti-Coronavirus-Activism (Notes: Field time: 10-16 April 2020, N=1,500 respondents (14 years and older), data weighted, representative for the Austrian resident population).

But what drives these people to go as far to denouncing their fellow citizens? In order to get to the bottom of the motivations behind this, further questions from our survey were used. First of all, we investigated whether and to what extent this form of Anti-Coronavirus-Activism is related to the respondents' danger perception, i.e. to what extent it correlates with their assessment of personal and collective health and economic danger. In addition, we analyzed to what extent the perceived sense of community plays a role in the willingness to report non-compliance with lockdown measures. Sense of community is the assessment of social cohesion in the country during the crisis situation (see appendix for question wording and notes on index formation).

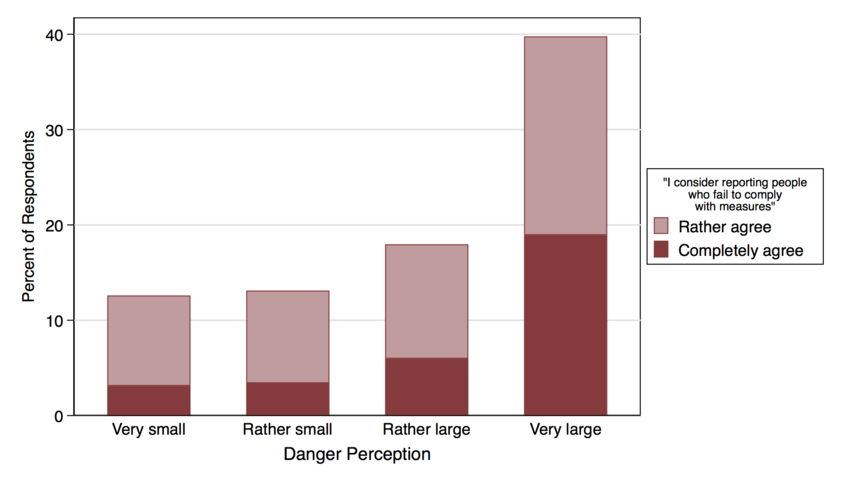

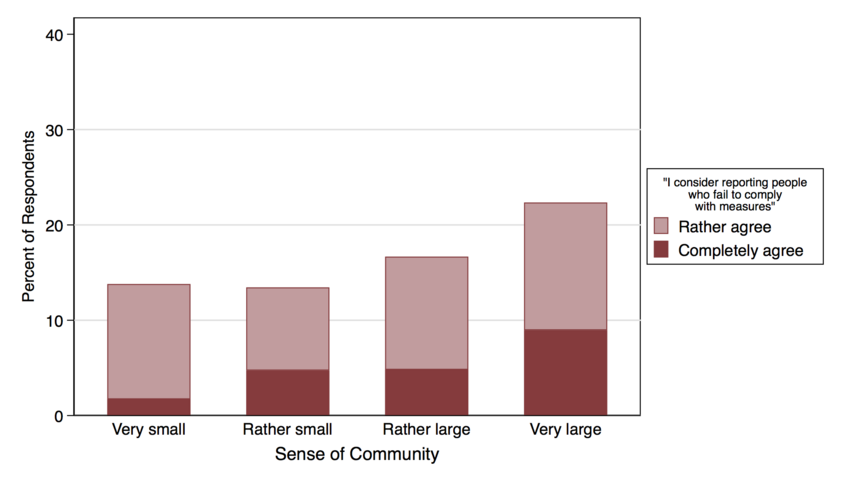

In both cases, we can see a positive correlation (see Figure 2a and Figure 2b): the higher the perception of danger and the sense of community, the greater the willingness to report other people to the authorities in the event of non-compliance with lockdown measures. For example, only 12.6% of people with very low danger perception would report others to the authorities. For those with very high danger perception, however, the figure is just under 40%. The contrast is somewhat weaker when it comes to the sense of community: if the sense of community is very weak, only 13.8% of people would report their fellow citizens to the authorities, compared to 22.4% of people with a very high sense of community.

Figure 2a: Effect of danger perception on the willingness to report people who do not comply with measures to the authorities (Notes: Field time: 10-16 April 2020, N=1,500 respondents (14 years and older), data weighted, representative for the Austrian resident population).

Figure 2b: Effect of the sense of community on the willingness to report people who do not comply with measures to the authorities (Notes: Field time: 10-16 April 2020, N=1,500 respondents (14 years and older), data weighted, representative for the Austrian resident population).

Let's stop calling them snoopers

Summing up, we can say that the actual proportion of the population that would consider reporting lockdown violators to the authorities is relatively small in Austria. We have also been able to show that the motivation behind this behaviour may be less fuelled by denunciation or nagging than by genuine concern about the dangers of the virus and its spread. The motivation behind the currently increasing number of police complaints seems to be due to a different danger perception and a different level of perceived sense of community. The danger perception plays an even greater role than the sense of community. Of course, unfounded and maliciously motivated police complaints cannot be completely ruled out, but our results indicate that it is unfair to the sum of people who file complaints to continue and call the “snoopers” (note that the German word is for this behavior is much more pejorative).

Ultimately, however, the question arises as to whether filing a complaint against neighbours or unknown persons is the best and most sensible solution in such situations. Whether a report to the authorities is useful is also related not least to the extent to which the observed action contradicts the aim of the lockdown measures, i.e. prevents the containment of the virus. One should bear in mind that not every small talk on the street between acquaintances who meet each other by chance immediately develops into a ruthless "street party" among Coronavirus sceptics.

Jakob-Moritz Eberl has been a post-doc at the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna since April 2017 and a member of the Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES, Media Side) since 2013. He is also an associate researcher at the Vienna Center for Electoral Research (VieCER) and deals with questions on media effects, media trust and voting behaviour.

Julia Partheymüller works as Senior Scientist at the Vienna Center for Electoral Research (VieCER) at the University of Vienna and is a member of the project team of the Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES). She received her doctorate in social sciences at the University of Mannheim and studied political science at the Free University of Berlin and the University of Hamburg.

Noelle Lebernegg is a University Assistant (Prae-Doc) at the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna and an associate researcher at the Vienna Center For Electoral Research (VieCER). She focuses on the impact of political communication and media on public opinion and voting behaviour.

David W. Schiestl works as a doctoral student at the Institute for Economic Sociology. His research focuses on the areas of labor market, migration, organization and social psychology.

Related Blog Posts

- Blog 4 (EN) - Old and New Media: Media Use in Times of the Corona Crisis

- Blog 12 (EN) - Most people take the situation seriously. But who are the Coronavirus skeptics?

- Blog 21 (EN) – Old And New Media: Disinformation in Times of the Corona Crisis

- Blog 40 (EN) - Audience Expectations of Coronavirus Reporting: From Watchdog to Lapdog?