12.05.2020

Austrians remain divided about Universal Basic Income

- Overall, the COVID-crisis has not increased support for unconditional basic income (UBI) in Austria.

- Among other groups, self- and unemployed people, as well as students, are more likely to be supportive of a UBI than the average. Those who already receive a stable, risk-free, and regular income are more likely to be opposed.

- With a view to the labour market situation in the current crisis, the only group predominantly in favour of a UBI are people who recently lost their job. Among the strongest opponents are those whose nature or extent of employment has not changed as a result of the crisis, or people who are working more now than they did before the crisis.

By Lukas Schlogl and Barbara Prainsack

In most general terms, an unconditional basic income (UBI) is a tax-financed, fixed amount of money paid to each individual citizen that covers the basic costs of living. Due to the increasing automation and digitalisation of work, calls for a UBI have become louder in many countries in recent years. Record levels of unemployment caused by the COVID crisis in recent weeks and months has further fuelled the debate. Even Pope Francis recently remarked that perhaps now was the time to consider a basic income. And a recent EU-wide opinion poll suggested that 71% of Europeans support the introduction of a universal basic income.

How do Austrians view the introduction of a UBI? Has the current crisis triggered a desire for a greater decoupling of income and work?

The prevailing mood

As part of the Corona Panel Study, we surveyed a representative sample of the Austrian resident population (n=1,515) on this topic. For the purpose of our survey, we defined UBI as noted above (in bold font), with the additional element that such a UBI would replace many social benefits. This means that elicited views on a welfare-substitutive (non-additive) form of UBI. Respondents were asked to indicate on a four-level scale their overall support for such an UBI in Austria.

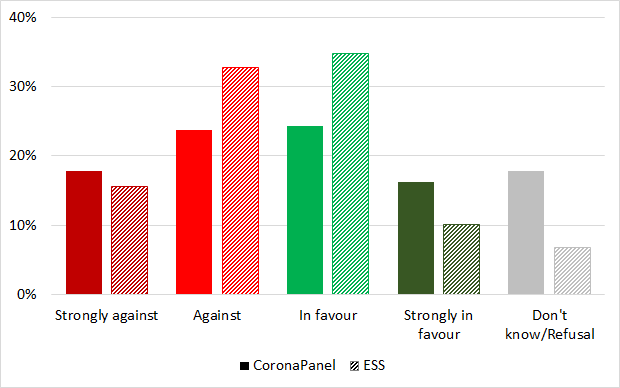

The results of the survey show, once again, that the topic is polarising. Roughly the same proportion of respondents were in favour of a UBI (40%) as were against (42%) (see Figure 1). But a large portion was undecided: almost one in five (18%) respondents said they did not know, or refused to answer.

Compared with data from the 2016 European Social Survey (ESS), the level of agreement versus disagreement has remained roughly the same. Only the degree of approval or rejection has shifted slightly: compared to 2016, in our new survey, more people were “strongly” in favour, or “strongly” against, than merely in favour or against. The mean values of the statement scale in the two surveys are almost identical.

Figure 1: Responses to the question “Overall, would you be in favour or against such a UBI in Austria?”. Fully coloured bars represent data from our Corona Panel Survey (n=1,515), striped bars show the results of the ESS 2016 in comparison (n=2,010). The difference between “don’t know” and “refuse to answer” could be an artifact of the difference of survey instruments (Corona Panel: online survey, ESS: face-to-face), as suggested by previous research.

The income (in)security factor

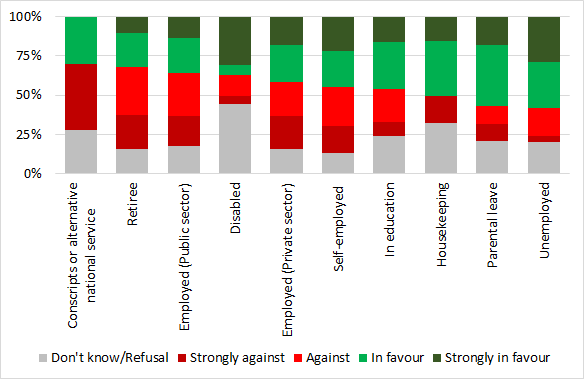

One of the characteristics of a UBI is that everyone receives the same amount of money, regardless of whether they work or not. Our analysis of the employment status of our respondents as of February 2020 (just before the crisis hit Austria) showed that during the crisis, approval of UBI has been higher among self-and unemployed individuals and students than among employees (especially in the public sector) and retired people. This means that those who already receive relatively risk-free, stable, regular incomes are more likely to be opposed to the idea of a UBI, while those in more precarious employment situations and those out of work tend to be more strongly in favour (chart 2, left).

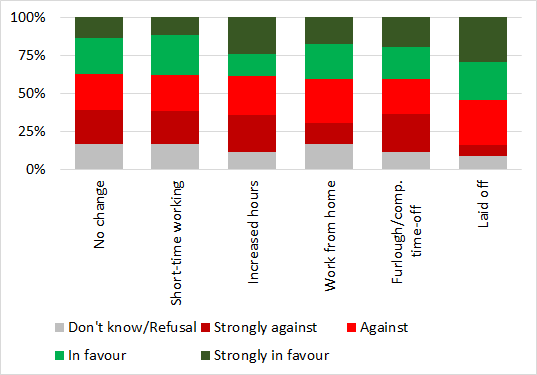

With a view to changes in employment status, people who had lost their jobs during the COVID crisis are the only group who are, overall, in favour of the introduction of a UBI. The majority of all other groups are against it, with the strongest opposition to a UBI found among those whose employment situation has not changed as a result of COVID - or who work even more now than they did before (Figure 2, right). Even in the ESS 2016, support for a UBI was significantly higher among job seekers in Austria than among other groups.

In sum, the COVID crisis has led to a rapid increase in unemployment, support for UBI has remained stable overall. A possible explanation for this fact is that the higher level of approval of UBI among unemployed people was offset by the opposite effect among other groups of workers (for example, those who now work more than before).

Figure 2: We asked respondents in April about their employment status in February, as well as their current employment status in April). The figure shows levels of (dis)approval to UBI according to employment status in February 2020 (left), and according to a possible change of employment status due to the COVID-crisis (right). Results for those in alternative national service (Zivildienst) need to be interpreted with caution as only three respondents fell into this category.

UBI defies conventional political categories

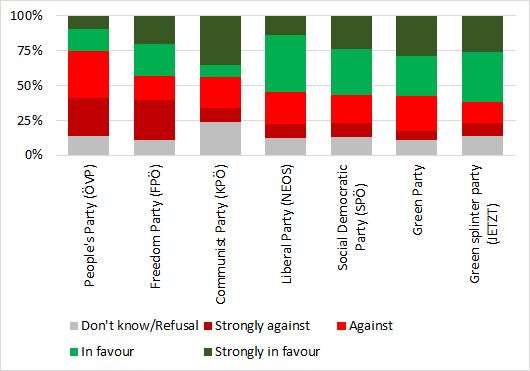

Views on UBI do not fit neatly into conventional political categories and camps. Among our respondents, we found support for UBI on the left and on the right of the political centre. The strongest support we found among (self-declared) voters of the liberal NEOS party and among those who said they voted for left and green parties (Figure 3). While voters of the conservative Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) and the right-wing Freedom Party (FPÖ) are most strongly opposed to UBI, sizeable minorities among these still held favourable views towards a UBI (note that a relatively high proportion of respondents shared their view on UBI but did not disclose their party preference which might skew these results).

Figure 3: Approval and disapproval of UBI according to self-reported party preference at the national election 2019

Looking into the future

While our data clearly show that there is no majority in favour of a UBI in Austria even at times of record unemployment, we must be cautious with drawing further conclusions. The pressure to introduce a UBI is particularly high in countries where there are only few social security instruments to prevent or mitigate income losses. This pressure is even greater in countries where people have to satisfy their fundamental needs, such as healthcare, child care, transport, education, and housing, at free-market terms rather than being able to access these in the form of public services.

In addition, to advance their cause, advocates of the basic income could use the fact that (fears of) unemployment have become widely shared social experiences, rather than being limited to marginalised groups of people. A fairly high number of people who do not yet hold a strong opinion on the subject might be swayed in one or the other direction. The last word on the subject of support for UBI in Austria during the COVID crisis may not yet have been spoken.

Barbara Prainsack is Professor of Comparative Policy Analysis, and director of the Centre for the Study of Contemporary Solidarity (CeSCoS) at the Department of Political Science at the University of Vienna.

Lukas Schlögl is a post-doctoral research assistant for Comparative Policy Analysis at the Department of Political Science at the University of Vienna. His research focus is on issues of technology, industrial and labour policy.